08 Apr Life After Cybercrime, One Day At A Time

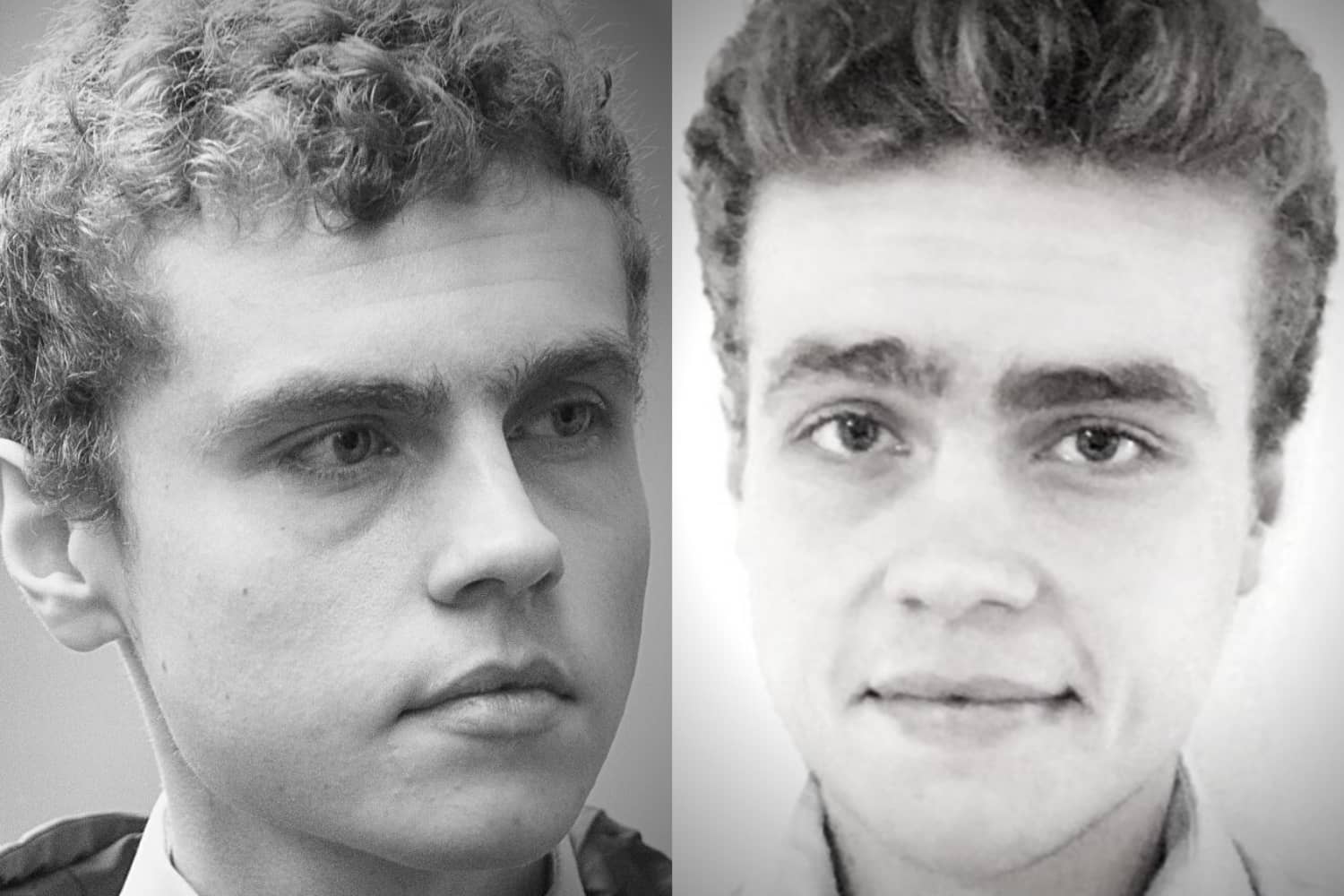

A year out of prison, Talk Talk’s infamous teenage hacker wants to use his skills for good

Melbourne, Australia – Apr. 8, 2022

It has been less than a year since Daniel Kelley was released from prison — and having had four years to reflect, he knows exactly how he started down the path that put him there.

It all started with World of Warcraft.

Rewind to 2011, when 13-year-old Kelley discovered the online game, which he grew to love so much that he was spending up to 14 hours a day on it.

“I became so professional that I basically managed to acquire a position within the top 20 players on this game,” he told Cybercrime Magazine. “And I remember queuing one night before the match started, and my Internet disconnected — and we lost the game.”

The culprit, he soon learned after conducting extensive research, was a distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack that had been launched by rival gamers to take the competition offline.

It was an increasingly common tactic — and it soured Kelley from the game he loved, which “was no longer about skill. I’d spent years developing this skill set and it was now essentially about who could DDoS each other the fastest.”

It was a slap in the face for a teenage technology enthusiast, who began intensively studying about computer operating systems, programming languages, web application development — and, ultimately, hacking.

“School taught me nothing in terms of computers,” he said. “Everything that I’ve learned was self-taught, and purely out of my own interests and passion…. My only interest was computers, and I replaced all the time I was putting into the game with research on different topics in cybersecurity.”

Cybercrime Radio: Life after cybercrime

Building a career, one day at a time

Hacking the world

Exploratory hacking followed, as Kelley began exploring the Internet from his home in Wales, UK, to see what he could do with his newly acquired knowledge and skills.

The early discovery of a code-injection vulnerability in a Microsoft platform led him to submit the finding to the company’s bug-bounty program, which verified his finding and posted his credentials on its website.

“At the very beginning of all this, the intent was really positive,” he recalls. “I had no real malicious intent; that came afterwards.”

The problem: invigorated by his success with the Microsoft vulnerability, Kelley began probing other sites to find and report more vulnerabilities.

“I had upwards of 100 vulnerabilities in loads of different websites,” he explained, “and I’d tried to report them because I was obsessed with the identification and the technical challenge.”

“But I tried to report the vulnerabilities, and quite often it was met with no response, or they would acknowledge my contact attempt and just left the vulnerability there. So I got really bored with getting no response.”

There are few other outcomes when a capable, intelligent, somewhat obsessive technophile gets bored — and Kelley quickly began down the path that led to his incarceration.

After immersing himself in IRC group chats, he began mingling with an increasingly adversarial hacker underground filled with budding cybercriminals who were, it turns out, much more interested in the vulnerabilities he had discovered.

“They were identifying vulnerabilities in websites, and conducting POST exploitation and seeing how far they can take it — whether they can gain internal access or steal data — and I pretty much decided to join them. From there, it spiraled into something really malicious.”

The coming years saw him developing and using a range of attack methods including web application vulnerabilities such as SQL injection, scripting vulnerabilities, and other attack vectors.

His goals ranged from probing networks to see how far he could go, to self-serving activities like DDoSing his school — Coleg Sir Garto shut down its systems, so he wouldn’t have to go in that day. But it was when he began blackmailing company executives for money that things fell apart.

Counting the cost

As a seasoned hacker, Kelley had secured a role managing a forum where cybercriminals would meet to exchange and discuss new exploits.

After a user posted data pertaining to the CEO of telecommunications company Talk Talk with a call for help in exploiting it, he took the data and tried to sell it to malicious hackers before ultimately embarking on a blackmailing spree that included company executives in the UK, US, and Australia.

With a few wins and many thousands of pounds’ worth of Bitcoin to show for it — including one £10,000 windfall from a company in Australia — Kelley faced the logistical challenges of being a 15-year-old trying to put large sums of cash into the bank.

“There was no real element of sophistication,” he recalls, “and I didn’t intend on laundering the money. I was very opportunistic, and wanted to see what I could get out of the situation.”

His life of isolation insulated him from the effects of what he was doing. “I had no real way to appreciate the ramifications of my actions,” he said, “and when it came to getting caught — it just wasn’t a variable in my head that I considered. I just used Tor and a VPN, and just sort of went about doing things.”

The CEO of Talk Talk, however, was far more acutely aware of the implications of being blackmailed — and the ensuing news coverage left Kelley “in disbelief…. It was almost like I was in some type of film. I had real issues identifying what I had done at that period of time.”

Kelley still isn’t sure how he got arrested, although he suspects authorities cross-matched his Bitcoin wallet address between his Talk Talk demands and emails sent to another company he was blackmailing at the same time.

Things got real very quickly, after a dozen police cars descended on the 16-year-old Kelley’s house and took him into custody on suspicion of blackmail. He was rapidly processed, and ultimately bailed on the condition that he not use the Python scripting language.

After four years on bail, however, the investigation expanded and in 2019 Kelley was sentenced to 12 years in prison based on more than two dozen charges — which was dropped to 11 charges after “extensive negotiation” — that were alleged to have cost over £100m in damages all told.

Around £70m of this related to his exploitation of the data of Talk Talk, which was also fined £500,000 — the largest penalty ever handed down by the UK Information Commissioner’s Office — for failing to take even basic security precautions that would have prevented the compromise of thousands of customers’ data.

Yet for Kelly, the outcome was more costly: UK authorities take blackmail very seriously, although the original 12-year sentence was reduced to just four years based on his work doing responsible disclosures, collaborating with CERT teams and government agencies, and other white-hat behavior.

Despite being sentenced to the high-security HM Prison Belmarsh — the same place where Julian Assange is being held and got married in 2019 — Kelley said he was treated “with respect” in view of computer hacking “not necessarily warranting negative behavior.”

“My time in prison was definitely horrible,” he said, “but it wasn’t as bad as it could have been.”

Now nearly a year out of prison, Kelley is working to find his feet again, working with a range of agencies and trying to figure out how to build a career in cybersecurity despite conductions that prevent him from using certain technologies for at least five years.

“I truly believe that I’ve reformed myself,” he said. “I have a completely different outlook on life, in contrast to when I was [13]. I’ve tried to use my skills in a positive way — and I think that’s all I can keep on doing, really.”

– David Braue is an award-winning technology writer based in Melbourne, Australia.

Go here to read all of David’s Cybercrime Magazine articles.